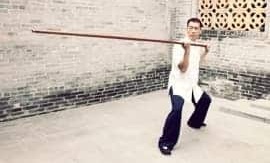

DANNY XUAN IS A RADICALLY DIFFERENT BREED OF INSTRUCTOR—A WING CHUN INDIANA JONES! LIKE THE FAMED CINEMATIC ARCHAEOLOGIST, XUAN TRAVELS TO EXOTIC LOCALES, ALL THE WHILE SEARCHING THROUGH THE PAST OF THE ART IN ORDER TO UNCOVER SECRETS THAT ENHANCE THE ART’S RELEVANCE AND VITALITY FOR MODERN DAY PRACTITIONERS.

While Xuan obviously respects tradition, he is equally wary of it. He champions Wing Chun as the child born of the understanding of natural laws and logic, with the science of physics and Chinese culture as its touchstones.

A devoted Wing Chun practitioner for over 40 years with a worldwide following of students, Danny Xuan downplays lineage and champions the cause of the individual practitioner. In Wing Chun circles he is a breath of fresh air, representing a truly new 21st-century approach to the art.

What got you interested in the martial arts and what arts did you study?

I first became interested in the martial arts as a kid living in the hills of the Himalayas where standing up and proving yourself by your fists was the norm and of great importance, so I began fighting at a young age.

In 1962, I took up Judo at age 11 and continued with it until the age of 15, when my family migrated to Toronto, Canada. In 1968, I joined the first Taekwondo school that opened in Canada. In 1970, I was introduced to Wing Chun, taught by a Hong Kong Chinese immigrant named Wong Siu Leung, who had originally learned Wing Chun from Grandmaster Moy Yat, and later from Grandmaster Wong Shun Leung. A couple of years later, I had the good fortune of meeting Sifu Nelson Chan, who had just migrated to Toronto from Hong Kong. He was not only Grandmaster Moy Yat’s top student but also his protégé and godson. I began to learn from him privately every day in addition to continuing my training in Taekwondo in the afternoons and then studying Wing Chun at night at the other school. I lived martial arts entirely from 1972 to 1975, training eight hours a day.

Did you continue with Wing Chun after 1975?

Yes. I moved to Vancouver in 1975 and taught Wing Chun until I met Sifu Winston Wan who was the top student of Grandmaster Lok Yiu, the second student of Great Grandmaster Ip Man in Hong Kong. Lok Yiu was the defender of Wing Chun against other martial arts in Hong Kong before Wong Shun Leung took up the mantle. I was with Sifu Wan from 1983 until I left for Canada in 1994. I then moved to Thailand and later to China, where I was unable able to find anyone with knowledge in Wing Chun that was comparable to either my teachers or myself, so I decided to explore Wing Chun knowledge on my own.

How did you do that?

Through reverse engineering—I looked at everything that I had learned up until then as being wrong until proven right. I subjected everything about Wing Chun to tests of force and logic. I studied Taiji, Qigong, physics and human anatomy to better understand the workings of the human body and how it connected with natural laws.

So, what is your perspective on Wing Chun?

First off, I don’t believe Wing Chun is a fighting style. For that matter, none of the martial arts are fighting styles. A style is a property of an individual, not a system. You may have your own style of golfing or boxing, but there is no golfing or boxing styles. Arnold Palmer and Tiger Woods have their own styles. Muhammad Ali and Tyson have their own styles. Each individual uses the fundamental tools and principles of the game in their own way. Similarly, fighting is just fighting, and each individual expresses it in his own way, according to his experience. Martial arts were created by individuals who experienced fighting and developed their own concepts of what a fight entailed and what was required to overcome an opponent.

How so?

These guys must have reviewed their fighting experiences and found some commonality, and designed training programmes to manifest the concepts. Some may have developed the concept of standing toe-to-toe and slugging it out, while others may have decided to move and jab. Some may have decided that kicking was the best tool because of leg strength and length, while others may have decided that takedowns and grappling would do the job.

To me, Wing Chun is just another training programme designed to manifest a fighting “concept”. The concept is based on a set of principles and these principles are expressed through the forms and exercises.

So, if Wing Chun is a concept based on set principles, why are there so many different Wing Chun families?

Basically, the principles taught in different Wing Chun families are the same. However, the approach, the path and the details vary depending upon how the principles are expressed and reached. Similarly, the principles of auto mechanics are basically the same from one car to another. However, the goals, designs and results can be radically different. Cars can be designed to be faster, to carry more people or use less fuel, etc. And this is simply a result of understanding and applying the universal principles that underpin the science of auto mechanics.

Similarly, the principles of some fighting systems are more valid than the principles underpinning others, and something special happens when a martial artist employs valid principles. And, in this respect, a system comprised of valid principles has a better chance of developing a good martial artist than a system lacking these same principles. By the same token, you can have a system with valid principles but lack the proper training programme to develop a good martial artist.

Can you give an example of this?

One of the weakest training methods is the repetition of preset drills designed to automate a student’s reaction to certain types of attacks in certain ways. Wing Chun’s uniqueness over other martial arts is the Chi Sao exercise, which develops contact sensitivity and reaction, allowing the practitioners to interact with each other differently every time. Thus, the predictability aspect is removed completely. This is a much more practical type of training that can be realistically and effectively applied in real-life situations that are preset drills where one partner throws an unthreatening attack and the other circles around him with multiple counter-attacks.

My approach to Wing Chun is to prepare the student for real-life situations by developing the skill of knowing himself and his opponent through contact and control. I teach the student to hold his ground and occupy his opponent’s. I teach him strong defence and offence through proper structure, grounding and alignment. I refine his motor skills and coordination so that he will not only properly use his torso and limbs, but every part of them.

I teach him to free his mind and become one with his opponent. I teach him not to let any preconceived ideas obstruct his free thought, and to act and react freely, without form, style or technique. I teach him to act instinctively rather than methodically or by rote. Musashi, Bruce Lee and other great martial artists understood this.

How do you get that message across to your students?

I provide my students bits of information instead of bytes of information. For example, I give them bits of information on how to execute a strong and effective Tan Sao, Bong Sao, or a punch, and let them freely group them as bytes according to a situation. I don’t put the bits together for them, such as Tan Da, for a preconceived situation such as an incoming hook punch. I provide them with the database to intelligently pull out the best pieces to solve the problem at that very moment.

One thing that I do differently from other teachers is that I show my students right from the start the goals or destinations they are heading for. Most students don’t know, and neither do their teachers. It’s like the blind leading the blind! Their teachers just throw hundreds of jigsaw puzzle pieces at them without showing them the finished picture on the box. That’s how they were trained, and that’s how they train others.

The finished picture of Wing Chun is a very holistic form of martial art. You can’t form the image without understanding the components that make up the whole system.

Give me an example of what you think is missing in the interpretation of Wing Chun by other Sifus.

Well, it is difficult to pinpoint one particular component because they’re all linked together but to give you a simple answer, I will say that they’re missing the Wing Chun culture. Wing Chun was developed in China, so it is deeply rooted in ancient Chinese culture. All of the historical and cultural influences at the time of Wing Chun’s development are embedded in the art. You’ll find Confucianism, Daoism, Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Chinese language, Sunzi’s The Art of War, Wing Chun history and characters—all of these make up the art. Without understanding the culture, you will never quite grasp the essence of the art.

For example, Wing Chun fellowship is based on Confucius’ teachings on family and filial values rather than Japanese Samurai culture and military rankings. Wing Chun’s concept of force is based on Daoism’s Yin/Yang philosophy. Wing Chun’s centreline concept is based on Traditional Chinese Medicine. Wing Chun’s choice of words in naming the forms and actions in Chinese are not only specific but also symbolic. Wing Chun’s concept of fighting is completely based on Sunzi’s The Art of War. Wing Chun’s historical events and feminine approach to martial arts derive from the characters involved in the founding and development of the art.

Without understanding these cultural and historical aspects of the art, one will never discover the full depth and wealth that the art has to offer. Moreover, if one rejects the ancient Chinese culture within the art, and brings in the contemporary culture of instant gratification, big egos, recognition, disrespect and the worship of money, then one not only destroys the art but, ultimately, oneself.

So, how are you going to get your perspective of Wing Chun across to those wishing to learn from you?

My way of teaching is difficult to get across to the masses or a large class. I’ve been teaching privately and with small groups internationally.

I was based in Thailand and China for 18 years until September of 2012 when I returned to Canada. I’m setting up my base in Bracebridge, where I’ll maintain a small group of students. Meanwhile, I will continue teaching privately worldwide, and conduct workshops just for the purpose of enlightening those seeking additional depth in Wing Chun.

Where are some of your students and workshop venues worldwide? I have serious students in Morocco, Spain, Belgium, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, Canada and China. I have online students in the US, England, Italy and other parts of Europe. I own a large property in southwest China where I often conduct workshops and retreats. It was designed for overseas students to live and train there for weeks or months.

Why locate your retreat in southwest China?

Because I believe it’s the location of the origin of Wing Chun—but that’s another long and controversial topic, best left for discussion at another time.