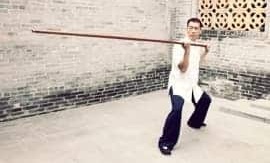

ALONGSIDE THE BUTTERFLY KNIVES, THE LONG POLE IS ONE OF THE MAIN HISTORICAL WEAPONS OF SOUTHERN CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS TRADITIONS AND IS IN HUNG GAR, CHOY LI FUT, AND WHITE CRANE.

While those styles have more understandable connections in usage and movement with the Long Pole, it is not clear how this weapon became a fundamental part of Wing Chun.

The Long Pole’s history is shrouded in mystery. It has been said to be the long oar used to push the boats alongside the small canals and rivers in the Pearl River Delta (including the areas of Guangzhou, Guangdong, Foshan and Hong Kong) during the Red Boat era. While this could have been one practical usage of the Long Pole, let’s dig more into its origins.

There are historical accounts of the Chinese military using poles and spears during the 17th century and accounts published in 1610 of Shaolin Temple monks using poles for fighting. However, the style of the Long Pole we know and use, nowadays, is most logically connected to how it was used as a weapon by civilian fighters in the Red Turban Revolt (1854–56) and the later Taiping Rebellion (1850-64), two Civil Wars that shaped the history of Southern China.

Many believe the rebellions that fought against the Qing Dynasty used the Long Pole for long-range fighting or from the boats, while knives were used for close-range. The knives were specially developed to fight against the Qing soldiers’ main weapons, poles and short spears, and that is why poles and knives are still paired in training against each other today.

According to many historical accounts, the Chinese militia and civilian fighters of the 19th century were commonly equipped with a bamboo helmet, a pair of Wu Dip Do (“Double Knives”), and a Lok Dim Boon Gwan that was thick at the bottom and thin at the top.

During the anti-Qing rebellions, the Qing Dynasty forbid civilians from carrying weapons, but a Long Pole could be seen as an everyday object. Ordinary-length poles could be stacked together to create long-fighting poles. This could also explain why the rebels’ poles were tapered, which would allow them to fit spearheads when needed, as the heavy ends would balance the weight. Their choice of the weapon also makes sense due to the low cost of producing the poles.

In today’s Guangzhou Wing Chun circles, it is common to hear the Lok Dim Boon Gwan was originally a spear that transformed into a Long Pole due to legal restrictions and the high cost of producing spearheads for civilian militias.

Nowadays, three main pole forms are practised in Wing Chun circles around the world:

• Ip Man’s Lok Dim Boon Gwan (六點半棍, “Six-and-a-Half-Point Pole”).

• Another version of the Lok Dim Boon Gwan in the Chi Sim Wing Chun tradition coming from Tang Yik.

• The Som Dim Boon Gwan (三點半棍, “ ree-and-a-Half-Point Pole”) practised by the Gulo village lineages.

These forms present differences in the technical aspects, length, and usage of the pole, though many people support the theory that the popular Ip Man form might derive from Tang Yik’s Long Pole form. A less well-known version of the Lok Dim Boon Gwan is the Yuen Kay-San version, which is popular with the Guangzhou area’s Wing Chun groups and their derivatives.

Other similarities can be found in the pole forms of Fujian White Crane style and in some Hung Gar lineages. While many styles use similar fundamental principles in their pole form, and most have seven core principles in number, the principles may differ from style to style.

Main principles shared by many styles include: Tai (“Raise”), Lan (“Bar”), Dim (“Point”), Kit (“Deflect”), Gwot (“Cut”), Wun (“Circle”) and Lao (“Receive”), which is considered the half principle.

In recent years, many Wing Chun practitioners prefer the usage of the Butterfly Knives as opposed to the Long Pole, since the Knives fit better into the conceptual ideas of Wing Chun in the way we perform the techniques and in the way we use the body.

Many find the long, low and side position assumed during most of the pole form both strange and difficult to perform. And it is difficult to find an indoor space in which to move a pole almost three metres long! It is also complicated to bring it to a park or large public space, unless you live close, or unless, like some rebels, you have a stackable pole that can be dissembled. (They sell those these days.)

While I agree that the three-metre Long Pole doesn’t seem like it immediately fits into the concepts and movements of Wing Chun, the situation is made worse by the wrong ways practitioners use the weapon nowadays.

Most practitioners use it similar to a Shaolin staff, with a lot of circular movements, instead of the straight and fast attacks that make sense, given the pole’s connection with the spear. Other practitioners believe the pole is merely a way to improve their strength as if the Long Pole was simply Wing Chun’s way of weight training.

Moving a three-metre Long Pole that weighs almost three kilograms is not an easy task, even for a short while, especially when you must focus on moving it with your limbs, simultaneously trying to harness explosive power. In fighting, conservation of energy is essential, so using it in this highly muscular manner isn’t efficient and wasn’t the way the Lok Dim Boon Gwan was designed to be used. In various manuscripts and books, the masters of the past referred to complex body mechanics and Internal ways of moving the body while training with weapons.

However, the common people that formed the militia in those turbulent times needed a fast and simple way to fight with weapons and used it only in a muscular way. They didn’t have the luxury of background, culture, and time to go through the slow process of training and mastering the body and the mind.

Unfortunately, most principles of proper body usage and mechanics were lost in most of the Southern Chinese martial arts due to the many rebellions and wars that escalated from the Opium Wars of 1839-42 and 1856-60 between Qing Dynasty China and Britain, through the Red Turban Revolt and the Taiping Rebellion; a continuous 25 years of war from 1839 to 1864 created a split in Chinese culture between North and South still felt today.

It is in the so-called Internal styles from the north of China that use a similar weapon (sometimes even a longer pole) that gives us a glimpse of how the pole was intended to be used in martial arts. In these styles, instead of moving such a long weapon solely with limb strength, the practitioner holds the pole so the bottom part is pressed against the hip on the dominant side. In this way, the practitioner allows the core of the body to carry the heavy weight of the Long Pole and move it. This creates a more powerful and controlled way to use the pole but obviously limits the range of motion if one is not aware of how to use the core and body properly to generate power for such a long weapon.

Luckily, many modern Wing Chun lineages have been trying to restore the usage of this wonderful weapon that, in the past, was considered the king of the poles—even superior to the divine Shaolin spear. Even though I have found some Northern China styles that demonstrate how to use the Long Pole in a practical way, those methods are not for everyone, as they require a precise control of the body, which takes considerable time to be mastered. But, I believe more people are rethinking their ideas about the Lok Dim Boon Gwan and accepting new ways to approach this often-misunderstood weapon. Perhaps, soon, a new era of respect and recognition will come for the Long Pole; it has languished in undeserved obscurity long enough.