JACK TAK FOK LING IS AN EARLY STUDENT OF THE LATE LEUNG SHEUNG (梁相), THE FIRST STUDENT OF IP MAN IN HONG KONG. HE STARTED HIS DAILY TRAINING WITH LEUNG WHEN HE WAS TWELVE. TOO YOUNG TO ABSORB MANY IDEAS TAUGHT DURING THE AFTERNOON CLASSES, HE DECIDED TO STUDY PRIVATELY WITH HIS SIFU ON SATURDAYS ALSO.

On Saturdays, Leung Sheung reviewed each hand with Jack and would teach nothing new to him until that hand was demonstrated properly in the Chi Sau format. At times, it took Jack several weeks to demonstrate a hand correctly. Fortunately, Leung Sheung used several effective drills to help him develop the many hands in the three empty-hand forms and the Muk Yan Jong.

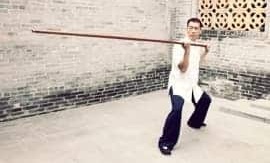

After graduating from the Diocesan Boys School, Jack was prepared to leave Hong Kong to pursue a college education in the United States. Realising that, Leung Sheung endeavoured to teach Jack the basics of the two weapon forms during the last seven months of his training. The daily training was intense.

After Jack started his career as a professor and university administrator, he only taught Wing Chun to a few individuals, who were already accomplished practitioners in Wing Chun of another lineage or in some other martial arts disciplines. He retired in 2015.

The Leung Sheung lineage seems to put heavy emphasis on stance development. Shouldn’t stance development be a standard part of Wing Chun training?

Developing a good stance takes work, and only certain groups of people want to learn that as part of traditional Wing Chun, so it’s standard for students not to have a root. Finding a Sifu that emphasises structure and roots training is rare because teaching someone to hit and throw fists is a lot easier! In Hong Kong, the basic training of proper roots and structure, which took many months in the early times, is virtually gone. Younger students have less patience to learn the seemingly boring and strenuous “stuff”—they just want to learn to fight quickly and then use it.

I went to a guy’s studio, and he has a student who’s been studying for three months, but he’s finished Biu Ji and was doing the Wooden Dummy, and I wondered, “How does this happen?” I turned to his Sifu and said, “I was still in my Horse after six months.” It turns out the student went away and learned the forms from somebody else then came back. What’s a teacher supposed to do? Teach him or not? I think that’s a dilemma, now that there are so many teachers.

It’s very important to be willing and able to tell a student they’ll learn the foundations from the beginning. My teacher said, “Jack, do this correctly. You can’t teach for money or you will find yourself not doing very well.” He told me to practise on my own, but not to teach professionally. You won’t find many of Leung Sheung’s students teaching professionally. In Hong Kong, most started teaching after retirement, with only one or two exceptions.

Your training sounds like it was rigorous. How do you approach passing along traditional skills without alienating students?

The instruction requires both toughness and support. The balance is difficult to find. Some teachers are too supportive, and there is no focus. Others are too tough, and still, others just say, “Do this” then walk away. Each approach has a few talented individuals rising to the top, not because of the teaching or the teacher, but because they have grit. So, it’s not a good way. You can look at all these good teachers and fighters—look at their students. You can’t generalise and say most have talent. A few, maybe, but most are average.

My Sifu was really a teacher-father. He would have me practise things he knew I couldn’t do, but he would always encourage me to keep going. I remember these experiences, and I consider how to replicate this process with my students.

It’s a hard thing for some to acknowledge that the pedagogy of Wing Chun is very much grounded in a one-to-one relation. My ability to transmit what I’m talking about comes from touch. So, with a lot of students at once, I’d not be able to do that. My teacher had a regular group and a smaller inner group, and even then, he touches people he prefers more than others. The more your Sifu likes you, the more you will get access from his heart. It’s a tricky thing. If you can’t speak the language, that’s one strike against you, and another if you are from a different circle or from another town—so by the time it’s said and done, you may seldom touch his hands. It isn’t uncommon to meet someone who claimed to have studied with Ip Man for many years and, in actuality, hardly ever touched his teacher’s hands! That person was probably trained by his or her Sihing and had hands unlike Ip Man.

You’ve talked about challenging your Sifu to test your Gung Fu. Can you elaborate on that, please?

You are supposed to challenge your Sifu and demonstrate the teacher is teaching correctly. There was an interesting tradition where you aren’t allowed to touch (your teacher). If you are talented and you show you are good, the teacher will make you a special student. If you don’t, you go back to the pool. When we were kids in Hong Kong, we were fighting a lot, so the idea of challenging your teacher was popular. We were all eager to see if we could do something against Sifu. In three or three-and-a-half years, you challenge him and he beats you up (Ha-Ha!). Then he tells you to start over, go back to Chum Kiu, and you need more of this and this.

I want my students to do better than me. Objectively, you guys are younger than I am. The idea of a 72-year old guy putting a hand on you and you can’t move? That’s ridiculous if you think about it. You have to be respectful, but you must also show you can apply the principles of your training. Once you have faith in these principles, you test them—do they translate to actual fighting? To gain that sense of trust that you can do it in a relaxed way or from an inch away, to hit someone and hurt them or drop them, most of us think, “Oh, I can’t do that. He’s so big! How can I move this little bit and make him fall down?” We don’t believe that.

In Hong Kong, it wasn’t a problem to find a fight or a challenge match. Knock the guy down. Then you come back, and you have proof the hand works. But I ask, how many people believe this hand would stop a fight? If you don’t believe you can do it, you won’t trust it. You must believe these small movements can hurt in a very decisive way. I have no problem. I know I can hurt you fast with little movement, so I need not prove it to you. I just keep practising to maintain that ability. Then, I want my students to develop that ability. Always think about Ip Man as the example—think about him beating us all!

If someone were preparing for a challenge match, what would they practise?

Chum Kiu is the platform. It’s important to train the back leg well, and the saying is, if you are preparing to fight in a match, then practise Siu Nim Tau and Chum Kiu many times and Chum Kiu drills/turning. That’s it. Don’t focus on practising Biu Ji. Practise the footwork. When you feel integrated as one piece and rooted with your hands floating, it’s a different feel.

People no longer challenge each other. In Hong Kong, challenge matches were outlawed in 1969 because people were getting hurt. The police couldn’t differentiate between a martial art challenge match and a gang fight, so they just outlawed it all. What that did, essentially, is that now learning whether you can fight is narrowed down to what you do in the school. The school is concerned about you hurting each other, but it’s not about fighting each other. We must overcome a sense of fear and have confidence that, when we punch, we won’t fall apart. Anybody who has been in a fight will know.

You’ve some interesting insights into the term, Chung Chi. Would you be willing to share some?

I heard Mak Bo coined the term, Chung Chi. Sifu Leung Sheung never used the term. But do you know what that term was for? Where Mak Bo might have got it from? It’s from the Knives form. Chung 冲 means “to charge” and Chi means, “to stab or penetrate”. I was also told that Mak Bo told practitioners not to Chung by pushing with their shoulders and upper body. One should charge forward (Chung). Chi means to stab or penetrate. 刺—stab/thrust/sting—so Chung Chi is using your roots to stab into the centreline. It cuts straight into the heart.

One of my Sihings was known as a butcher (he was not one in real life). When he held the knife, you could hit it and it never moved. The back-weightiness of the stance lets you use Chung Chi. We trained nothing but this stance for two months.

I visited with Julian Cordero, a student of Moy Yat, recently. He was very nice and gave me a pair of bamboo knives. When we were in Hong Kong with Ip Man and Leung Sheung, they were very particular about not fighting each other with knives. With metal weapons, you can get hurt. You want to use a real knife for the training of your wrist and other things, but there is no sense carrying one around. Wong Shun Leung trained the knives with a Taoist monk, who was one of his important students, but after a while, even he said he would not teach people to fight with knives anymore because it’s dangerous. It’s interesting to see that, in the United States, everybody wants these sharp knives and I say, “Gosh, you are going to chop yourself with them! You’ll cut your hand off!”

Do you have any parting advice or wisdom for people studying Wing Chun these days?

Train hard and take no shortcuts. Listen to your teacher and work on developing your skills, especially on rooting, structure and developing the source of power. They are very important because, without them, you will have only limited skill and confidence. Enjoy your training. The path is the reward.